Japanese Philosophy

Japanese philosophers have historically interacted intensively with a multitude of philosophies outside their native boundaries—most prominently Chinese, Indian, Korean, and Western. So they have benefited from a rich trove of ideas and theories on which to draw in developing their own distinctive philosophical perspectives. As a result Japanese philosophers have always been acutely attuned to the intimate relations among culture, ways of thinking, and philosophical world views. An island chain twice as distant from its continental neighbors as Britain is to its own, Japan escaped successful foreign invasion until 1945. Accordingly, it largely negotiated its own cultural, including philosophical, development without an alien power forcibly imposing on the archipelago its own religious world view or philosophical theories. The early twentieth-century academic philosophers in Japan, for example, were so well educated in the world’s texts and theories, many in the original languages, that they were among the most internationally informed philosophers of their time.

Without foreign ideas being coerced on them, Japanese thinkers had the luxury of alternatives outside the binary of simple wholehearted acceptance or utter rejection. New theories from abroad could be tried and, if need be, experimentally modified before making a final decision about endorsement. Sometimes a foreign philosophy might be seen as supplying raw material to be fashioned to serve ongoing native philosophical enterprises. In other cases a new philosophy might be imported whole cloth to either supplement or supplant a home system of thought. Because of those circumstances, Japanese philosophers acquired skill in analyzing foreign ideas by examining the cultural assumptions behind them to determine their potential implications if they were to be adopted into their own culture.

Against that backdrop, this article explains Japanese philosophy in five sections. Section 1 considers how Japanese have traditionally understood philosophy to be a Way (michi) of engaging reality rather than a detached method for studying it. The next section lists some patterns of analysis that are hallmarks of that Way of Japanese philosophizing. Section 3 identifies five distinguishable traditions having had a major impact on Japanese philosophy, explaining a few central ideas from each. Section 4 surveys how those five traditions have evolved and interacted over four major periods of Japanese history from ancient times to the present. Section 5 concludes with a few themes given special emphasis in Japanese philosophy that might be provocative to philosophy at large.

- 1. Philosophy as Engaged Knowing

- 2. Hallmarks of Japanese Philosophical Analysis

- 3. Five Fountainheads of Japanese Philosophy

- 4. Historical Periods of Philosophical Development and Interaction

- 5. Possible Contributions to Philosophy at Large

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Philosophy as Engaged Knowing

Most Japanese philosophers have assumed the relation between knower and known is an interactive conjunction between the two rather than a bridge spanning the disjunction between what is in the knower’s mind and the known which stands outside it. The Japanese philosopher is thus more likely to be viewed as a person who tries to fathom reality by working within it rather than one who tries to understand it by standing apart from it. In other words, the Japanese philosopher’s project more often involves personal engagement than impersonal detachment. The difference in emphasis between traditional Japanese philosophy and modern Western philosophy became clear to the Japanese when the latter was first introduced into their country in full force in the mid-nineteenth century. A crucial issue for the intellectual leadership of the time was how to identify in Japanese what the Westerners called philosophy. Wanting to assimilate Western philosophy along with other aspects of Western culture, the architects of Japanese modernization wanted to give the field its own Japanese name, rather than treating it as a foreign term pronounced phonetically.

To capture the philosophical sense of wisdom (-sophy), they picked a likely candidate from the classical East Asian tradition, namely, tetsu. More provocative, though, was their choice for the other part of the neologism, namely, gaku. That word also had a classical pedigree: it signified learning, especially in the sense of modeling oneself after a textual or human model (that is, a master text or a personal master). Probably more significantly, though, the term gaku at the time was prominent in neologisms for disciplines in the newly established Western-style universities, functioning as an equivalent for the German Wissenschaft. Hence, it rendered the -ology suffix of fields like biology or geology as well as the humanistic “sciences” (Wissenschaften) like history or literary studies. By this protocol of nomenclature, the Western discipline of philosophy came to be called in Japan by the compound word tetsugaku and academic philosophers were (and still are) called tetsugakusha, that is, “ones who partake in the Wissenschaft of wisdom.”

The salient point is that the label chosen was not a more traditional term like tetsujin, “wise people.” A word like tetsujin might have more closely approximated the original Greek meaning of the philosopher as a “lover of wisdom” than does tetsugakusha, which suggests something more like a “scholar of wisdomology.” As a result, we might say tetsujin better refers to the premodern Japanese sense of the philosopher, that is, a sage who has mastery in one of the traditional Ways (dō or michi) such as the Way of the buddhas, the Way of the Confucian scholarly sages, the Way of the (Shintō) kami, or even one of the Ways of the traditional arts such as calligraphy, tea ceremony, pottery, painting, flower arranging, or any of the various martial arts. (Traditional Japan used a variety of terms for the sagely master; for convenience in this article tetsujin will appear throughout.)

In effect, by creating the new term tetsugakusha instead of drawing on an already existing term from their own tradition, the Japanese were drawing a distinction between two species of understanding and two forms of philosophizing. One species of knowers aspires to a scholarly (“scientific”) detachment that mutes personal affect with the aim of reflecting external affairs as they exist independently of human ideation. That kind of understanding is the goal of the Wissenschaften—the empirical sciences, literary criticism, studies of history, and social sciences—that define most departments in the academy alongside philosophy.

The other species of understanding characterizes those who personally engage reality, transforming themselves and reality together into a coherent and harmonious whole. That more traditional Japanese sense of understanding transcends mere skill or know-how, it should be noted. To be a Confucian sage or a master calligrapher is not simply to be proficient in technique (any more than being a logician in the West is simply knowing how to construct a syllogism). Although rigorously disciplined in their early training, the members of the engaged knowing family of philosophers eventually go beyond fixed templates and regimens to respond creatively to what-is. When engaged understanding prevails, the knower and known collaborate in an act of innovation rather than simple discovery. From the Japanese standpoint, in their praxis as philosophers, the tetsugakusha are akin to how geologists understand clay whereas the tetsujin are akin to how master potters understand clay. The geologist acquires scientific knowledge (geology) to forge an external relation between the knower and the clay, each of which preexists the knowledge and basically remains unchanged by the knowledge (a Wissenschaft is typically grounded in the descriptive). By contrast, the knowledge of the potter is expressed in, by, and with the clay as an interactive project (the masterwork of pottery). Both the clay and the “bodymind” of the potter are transformed in the act of engaged wisdom. For the tetsugakusha, philosophy bridges the philosopher’s connection with reality; for the tetsujin, on the other hand, philosophy is the Way the philosopher and reality are purposively engaged with each other and transform each other. For the tetsugakusha philosophy is a link the self creates to connect with the world; for the tetsujin philosophy is a product created out of the mutual engagement between self and world. The distinction parallels what Henri Bergson characterized in the opening pages of Introduction to Metaphysics as two ways of knowing: “moving around” an object as contrasted with “entering it” (Bergson 1955, 21).

2. Hallmarks of Japanese Philosophical Analysis

2.1 Internal Relations

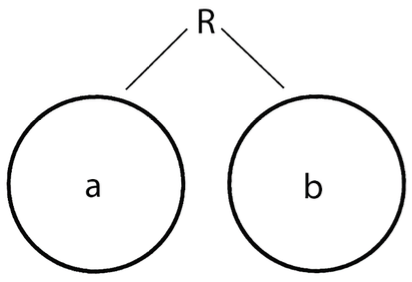

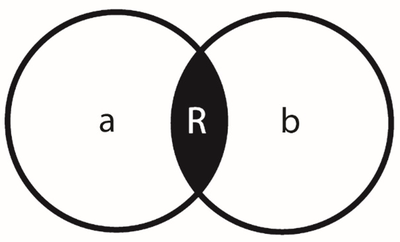

When Japanese thinkers assume two items are related (whether the items be physical entities, ideas, persons, social structures, etc.), they commonly begin by examining how the items internally overlap (how they interrelate) rather than by looking for something additional (a third item whether it be another thing, idea, force, or whatever) that externally connects or bonds them. The simple diagrams below indicate the chief difference.

|

|

|

Figure 1: External Relation |

Figure 2: Internal Relation |

Figure 1 shows a and b as discrete entities in an external relation represented by the extrinsic linking agency of R. Figure 2, by contrast, shows a and b as internally related entities such that R denotes what they share, what intrinsically conjoins them. In the case of the external relation, if the relation dissolves (or is omitted from the analysis), a and b each retains its own integrity without loss. Only the context of their connection disappears. In the case of an internal relation, on the other hand, if the relation dissolves (or is omitted from the analysis), a loses part of itself, as does b. For instance, as a legal arrangement, marriage is an external, contractual relation into which two individuals enter. Should that arrangement end, each of the pair returns to his or her originally discrete individuality and attendant rights. As a loving arrangement, however, marriage is an internal relation in which two people share part of themselves and should the love connection dissolve, each person loses part of what one had formerly been, the part that had been invested in the other. As Emily Dickinson (1884) wrote after losing a beloved friend, she became a “crescent” of her former self. (See the entry on relations for further discussion of the external/internal distinction.)

When Japanese philosophers emphasize engaged over detached knowing, their treatment of standard philosophical themes assumes distinctive nuances. One example will illustrate. Because of its roots in praxis, Japanese philosophy approaches mind-body issues differently from how they have typically been addressed in the West, especially the modern West. As the postwar philosopher, Yuasa Yasuo (1925–2005) analyzes in detail (Yuasa 1987), the preference in modern Western philosophy has been to think about the mind and body as discrete (that is, as external to each other) and the issue then becomes what connects the two. If no third external connection can be found, the only obvious alternative is to eliminate the dualism by reducing one of the polarities to the other, for example, by making the mind an epiphenomenon of the body. Yuasa found such formulations of the mind-body problem alien to the Japanese philosophical tradition, both ancient and modern.

Japanese philosophers have customarily taken the view that the body and mind may be distinguished, but they have assumed from the outset that their relation is internal rather than external. That is, the mind and body cannot be completely separated without violating their essential character or function. If we envision body and mind as a single complex of two intersecting circles (call it bodymind to capture the sense of the Japanese compound term shinjin), then without the somatic conjunction, the mind is not fully the mind and without the mental conjunction, the body is not fully the body. Accordingly, Yuasa argues, Japanese philosophers have throughout history typically searched not for what constant connects the discrete mind and discrete body, but instead, how the bodymind functions such that the interrelationship between the somatic and mental aspects may increase. That is, the focus has been how disciplined study and praxis enables the two circles to overlap increasingly in the direction of unity.

That approach implies that the bodymind relationship is a changing internal relationship rather than a fixed external one. In learning to play the piano, for example, Yuasa says the novice has “the mind lead the body” to memorize the keys, but as the pianist becomes proficient, “the body leads the mind” so that it seems the “fingers know where the keys are” without the intrusion of conscious thinking, leaving the mind to concentrate more fully on the music itself. As the two circles more fully merge, the bodymind becomes capable of holistic function. That unification enables further creativity and insight—the point when the music, the mind, and the fingers touching the keyboard become a single act. That pathway to increasing bodymind unity explains how praxis and discipline are prerequisite to free expression. Yuasa explains how this integrative bodymind phenomenon is treated in various Western as well as Eastern theories including neurology, the psychology of conditioned response, psychosomatic medicine, depth psychology, phenomenologies of the body, Indian Ayurvedic medicine, kundalini yogic praxis, Japanese theories of artistry, and East Asian models of ki (qi in Chinese) within medicine and the martial arts.

Yuasa concludes that philosophy would be well served by leaving the rarefied pure and distinct abstractions of Cartesian metaphysics and its theory of the substantially discrete body and mind. By focusing instead on the dynamics of bodymind as a single fluid system, the dualism inherent in the classic Western mind-body problem would dissolve into an engaged study of the Way of bodymind: its cultivation, transformation, and its links to praxis, performance, holistic health, and creative expression. Yuasa’s philosophy exemplifies how contemporary Japanese thinkers may constructively engage Western thought while drawing on strands of their own premodern traditions. As we have seen, his analysis shows how a relation (in this case that between mind and body) that is commonly assumed to be external in modern Western philosophy is understood quite differently when it is assumed to be internal. This difference is typical not only of Yuasa, but also more generally of Japanese philosophizing at large.

Consider also how highlighting internal relations would affect ethical problems involving self and other (whether the “other” is another person, a group, a thing, the natural world, etc.). Most Japanese philosophers tend to pose the fundamental question not in terms of what principles or calculus of consequential considerations define the ideal relation spanning the two. Instead their analyses more commonly begin from a consideration of what the self and other intrinsically share such that there is an original relationship at all: What is the common ground giving rise to the relationship? That is, ethics is not about making relations but about discovering interrelations.

Similarly, in aesthetics the general modus operandi for the Japanese philosopher is not to explain art as establishing extrinsic contexts or criteria that connect artist, medium, creative intention, audience, and the work of art (whether the work be poetry, painting, or a dramatic or musical performance). Instead the Japanese philosopher delves immediately into the in medias res of the work of art as the presentation of a single interresponsive field (often called kokoro) out of which that whole cluster of aesthetic components takes form. (See the entry on Japanese Aesthetics.)

To take one final example, in his ethico-political philosophy, Watsuji Tetsurō (1889–1960) explicitly rejected as a starting point the social contract theory of the modern West (Watsuji 1996). As a way of theorizing the meaning and purpose of the state, a social contract is conceived as an external relation made by discrete, independent individuals. Watsuji’s critique was that even a thought experiment should begin with an understanding of human existence based in fact. Human being originates not as an individual, but as a fetus interdependent with its mother and once born, the baby is fully dependent on its mother. Only subsequently does it develop individuality and independence, but even then it is in transition to becoming a socialized human being. To understand ethics and politics, Watsuji argues, even a thought experiment must recognize the inherent relations intrinsic to, and constitutive of, human being in that ongoing process, what he called a dialectic of interpersonal betweenness or being in the “midst of the interpersonal” (hito to hito no aidagara) that precedes the polarization into either individual or collective. (See the entry on Watsuji Tetsurō.)

2.2 Holographic Relation between Whole and Part

Models of reality built on external relations often resemble a mosaic in which individual entities are like tiles whose meaning in relation to the whole can only be determined by applying an extrinsic blueprint or template representing the external relations linking them. Each individual tile in itself gives little or no information about how it relates to other tiles. By contrast, models of reality built on internal relations are typically more like jigsaw puzzles in which we discover the relation of one piece to another by looking more closely at the information already within each individual piece: its protuberances, indentations, and coloration. Each piece has within it the information about how it links with its adjacent pieces. In some instances the configuration within the internal relation is even more revealing such that each piece has information not only about adjacent pieces, but also about all the other pieces in the whole. That paradigm can be called holographic in the etymological sense that the whole (holo-) is considered to be inscribed (-graph) in each of its parts. That is, the whole is not simply made of its parts, but also, each part contains the pattern or configuration of the whole of which it is a part. Such holographic relations between whole and part are common in Japanese philosophical systems.

In the West the holographic paradigm permeated animistic cultures tracing back to prehistoric times and persisted in the later magical arts wherein a fingernail or hair could give a wizard or witch power over the whole person from which the part was pilfered. It continued in the cult of relics throughout the Middle Ages. But the Enlightenment’s rationalism stripped the holographic paradigm of its ontological connections, restricting it to being no more than a figure of speech (such as a metonym) or other form of conventionalized symbol. In general the Western intellectual tradition limited holographic thinking to the literary (e.g., William Blake’s universe in a grain of sand) and the psychological (e.g., Freud’s symbolic dream analysis), rather than the philosophical.

More recently, however, in a scientific world increasingly attracted to frames of recursiveness, fractals, the multiple expressions of stem cells, and so forth, the holographic paradigm has once again begun to have ontological and not just figurative relevance in the West. To a forensic scientist, for example, a drop of blood or a single hair from a crime scene, is not only part of a person’s anatomy, but is also an item inscribed with the dna pattern of the person’s entire anatomy. The relevant contrast is that in the history of Japanese thought the holographical paradigm of the whole-inscribed-in-each-of-its-parts never went out of philosophical fashion as having potentially ontological significance. It was never demoted to the status of being only a primitive, magical, or metaphorical way of engaging the world. Indeed, holographic relations often figure prominently in many Japanese philosophical theories.

Two Western misinterpretations of the political theory behind Japan’s imperial polity illustrate the point. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Westerners first encountered the Japanese ideology of the emperor, they noted the emperor was referred to as kami, a term translated as “god” when it refers to a celestial deity. The (mistaken) inference was that the Japanese believed the emperor, like Yahweh or Zeus, was deemed to be a transcendent being in an external relation to the state and the people in it. That interpretation missed the internal relation between the emperor and the Japanese people that establishes their logical inseparability such that neither could maintain its full identity without the other. Thus, in the logic of the kamikaze pilot, dying for the emperor was not a simple act of sacrificing one’s self to a higher being or even a higher value. Instead, to die for the emperor could not be completely separated from dying for oneself and dying for all other Japanese. To deny that connection would reduce the pilot to a crescent of his full identity, that is, for him to die for the emperor was an act of self-fulfillment rather than self-sacrifice.

The second misunderstanding of the political theory behind the imperial system arose later in the twentieth century with Western intellectual historians influenced by Hayden White's theory of historical discourse and its analysis of tropes (White 1973). One claim was that in the nineteenth century Japanese Native Studies (Kokugaku) had developed a new form of historical narrative centering on the trope of kokutai. The emperor is the body, essence, or formation (tai) of the country, nation, and its people (koku). Thus the term kokutai applies to both the emperor and to Japan. The new ideological narrative, the critics claimed, deceptively used a metonym (the emperor as a part of the state used to symbolize the state) to claim the emperor is the state (Harootunian 1978). Despite its virtues on other counts (see the entry on philosophy of history, section 3.4), metahistorical criticism ill fits the Japanese situation inasmuch as it overlooks the long-standing Japanese emphasis on internal and holographic relations. That is, the internal relation between emperor and Japan establishes a holographic relation such that each person contains the configuration of the whole Japanese nation. From the standpoint of the traditional Japanese kokutai theory, to claim the emperor is really only a symbol or metonym for Japan is a category mistake comparable to saying the dna found in the blood at the crime scene is only a symbol or metonym for the perpetrator. The philosophical claim (leaving aside here the truth value of that claim) is that the relations among the emperor, the Japanese people, and the state are comparable to the relations among the dna, the blood, and the person from the crime scene. It is simply a false premise (and certainly not one assumed in the history of Japanese thought) that there is no possible sense in which the whole can be contained in one of its parts and that any such claim must be no more than a trope.

Another area where ignorance of Japanese holographic thinking has led to Western misinterpretation is in the so-called aesthetic of minimalism. Once we are attuned to the holographic paradigm it becomes clear that Japanese minimalism is not about eliminating the extraneous or omitting the unnecessary, but rather (as in the case of the forensic scientist) about focusing on the particular as revealing the whole from which it was taken. If we recall that the Japanese work of art is the creative presentation of the kokoro (the total interactive field that generates the artist, medium, and audience as a single event) then what is normally considered in the West to be the work of art is that precise point in the kokoro through which we can experience the configuration of the whole of the kokoro. Japanese minimalism does not exclude or eliminate; by focusing on the particular it enables us to attend to the whole aesthetic event that produces it and of which it is a part. To the discerning reader, the haiku with its meager seventeen syllables omits nothing; rather, it is holographic of the whole.

2.3 Forms of Assimilation

One response to encountering an opposing philosophical position or theory, a response common in the Western tradition from the time of the ancient Sophists, is to reaffirm one’s own position by refuting the other, revealing its inconsistencies or weaknesses. (This adversarial form of argumentation, including its rarefied form known as the reductio ad absurdum, is common in Indian philosophy as well and was introduced to Japan via Buddhism more than a millennium prior to any Western influence.) In Japan, however, a more common response to philosophical opposition has been to reaffirm one’s original view by assimilating into it what is central in the opposing viewpoint through a process of allocation, relegation, or hybridization. Very often in Japanese philosophical debates, the contenders compete in trying to absorb rather than refute the opposition. Cultural comparatists have noted that the Western game of chess is won by attacking the opponent’s pieces and capturing the king whereas the Japanese game of go is won by encircling the opponent’s stones until all are captured and none remain. To the surprise of the uninitiated Western philosophical reader, therefore, the skilled use of agreement and concession, rather than direct attack, may sometimes be the sharpest tools in the Japanese philosopher’s argumentative arsenal. It is important, therefore, to notice how allocation, relegation, and hybridization can help a philosophical theory gain dominance in the Japanese milieu.

2.3.1 Allocation

Allocation is the most compromising form of philosophical assimilation. Two opposing views are accepted without major alteration but conflict is avoided by restricting each to its own clearly defined disjunctive domain. A détente is negotiated such that each philosophy can function without opposition within its own discrete set of philosophical problems as long as it refrains from universal claims that its methods, assumptions, and conclusions apply to every possible kind of philosophical enterprise. For example, at times Japanese Confucian, Buddhist, and Shintō philosophies resolved potential conflicts by allocating social and political issues to Confucianism, psychological and epistemological theories to Buddhism, and naturalistic emotivism to Shintō. The Seventeen-article Constitution of Prince Shōtoku in the early seventh century is such an instance, using Confucian principles to define the political virtues and responsibilities of courtly retainers, the emperor, and the people, but following Buddhist models in discussing human nature and the cultivation of the introspective discipline necessary to control egoistic desires and unbridled emotions. Shōtoku’s document used allocation, in effect, to envision a harmonious world of Confucian social and ethical decorum inhabited by people trained in Buddhist psychospiritual introspection and discipline.

2.3.2 Relegation

Relegation assimilates an opposing view by conceding its truth even while subordinating that truth to being only a partial component of the original, now more inclusive, position. Usually the rhetoric is that the apparently opposing view is not really something new at all, but has always been part of the original theory, albeit perhaps not previously emphasized as such. As in allocation, the position of the other is fully accepted but in this case only as an incomplete part of the whole picture which, it is demonstrated, the original theory has contained all along (or at least could ex post facto be interpreted so). Of course, the rhetoric aside, a close analysis often reveals that the original theory actually expands its comprehensiveness to incorporate the competing one, but the end result is the same: the rival ideas are assimilated by being relegated to a subordinated place within the whole, thereby losing their force as an independent theory that can oppose the winning position. For example, Japanese esoteric Buddhism assimilated proto-Shintō ideas, values, and practices by relegating its kami to being “surface manifestations” of Buddhist reality. By that process, Shintō cosmology and rituals could be assimilated without change within the esoteric Buddhist system but only insofar as they were subordinated by means of a “deep” Buddhist metaphysical interpretation relegating their former proto-Shintō meanings to the superficial level of understanding.

2.3.3 Hybridization

Hybridization is a third form of assimilation that leaves neither the original theory nor its opposing rival theory intact. Instead, through their cross-pollination something completely new is born. A hybrid presents us with a new species of philosophy and although we can do a genealogy of its parentage, it cannot (unlike the cases of allocation or relegation) ever return to its earlier opposing forms. If we consider a biological hybrid like a boysenberry, which has a genetic parentage traceable to a loganberry and a raspberry, we cannot find the loganberry or the raspberry intact in the boysenberry. Once the hybrid is created, we cannot undo the crossbreeding; there are now three distinct species of berries. Analogously, in the process of philosophical assimilation, when true philosophical hybrids emerge, historians of philosophy may be able to uncover their genealogies, but the theories themselves can no longer be deconstructed back into their parental origins. As will be explained below, in Japan bushidō, the Way of the warrior, is such a philosophical hybrid born of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Shintō, but which became an independent philosophy of its own that in many ways served as a rival to its antecedents.

Next let us examine how Japanese philosophers use those forms of analysis in developing five originally distinct sources of philosophical ideas.

3. Five Fountainheads of Japanese Philosophy

3.1 Shintō

Three major philosophical sources have fed into Japanese thought since ancient times up through the present, two additional ones being added in modern times (that is, post-1868). First has been Shintō. In its archaic form, especially before its contact with the literary philosophical heritage of continental Asia, it is better termed proto-Shintō because it only loosely resembles what we now know as Shintō. Institutional Shintō thought did not significantly begin until the medieval period and today’s Shintō philosophy mostly originates in the Native Studies tradition beginning in the eighteenth century. That trajectory of Shintō doctrinal development continued with the rise of nationalism and ethnocentrism under the rubric of Shrine Shintō, the institutional arm of State Shintō ideology, which cast a pall on creative philosophical thinking from the early twentieth century until 1945. Postwar Japan has witnessed a range of renewed Shintō philosophies, some in the direction of a return to right-wing ideology, others toward a more liberalized version inspired by Western models of liberal Christian theology and comparative religious scholarship.

Proto-Shintō Animism and Naturalism

Proto-Shintō lacked philosophical reflection and even self-conscious articulation but is so named because today’s Shintō has often claimed (sometimes disingenuously) a resonance with its main values, ritual forms, and world view. Dating back to preliterate times, proto-Shintō was more an amalgam of beliefs and practices lending cohesion to early Japanese communities. As such it largely resembled religions in ancient animistic and shamanistic cultures found elsewhere in the world. Specifically, the material and spiritual were internally related so as to form a continuous field wherein the human and the natural, both animate and inanimate, were in an interactional, even communicative relation. Kami (often too restrictively translated into English as “gods”) manifested the power (tama) to inspire awe and could refer to anything ranging from a celestial deity to a ghost to a possessed human being to a spirit within a natural object to a wondrous natural object itself (such as Mt Fuji) to even a special manufactured object such as a sword. Although human interactions with kami might be either beneficial or harmful, there was no duality or conflict between good and evil forces. Even within human affairs wrongdoing was generally a violation or transgression of a taboo, regardless of whether the acts were accidental or intentional. Since criminality or sin was not a major consideration, the proper response was not so much guilt, repentance, or rehabilitation, but instead ritual purification. Spiritual and political leadership shared a common charisma allowing the political leader to serve sacerdotal roles in rituals that brought the community benefits and warded off danger. The rituals, often shamanistic in character, mediated the fluid boundaries between the heavens, this world, and the underworld as well as the realms of the animate, inanimate, human, and natural.

Although, as far as we know, there was no self-reflective philosophizing per se in the preliterate world of proto-Shintō, philosophical ideas introduced from abroad often took root most deeply when they drew support from some of its basic ideas and values. For example, proto-Shintō animism generally assumed we live in a world of internal relations where various forces and things can be distinguished, but in the end, they are never discrete but inherently interrelated in some way. Indeed because of that reciprocity, one might say the world is not simply what we engage, but also something that engages us. As we define it, it also defines us. Nothing is ever simply material without somehow also having some spirituality; nothing is ever simply spiritual without somehow also having some materiality. The ancient proto-Shintō creation myths recount how many parts of the physical world came into being through involuntary divine parthenogenesis. For example, the sun and the moon—both the physical objects and the celestial kami associated with each—came into being as the effluent of Izanagi kami’s eyes when he purified himself in a river after being polluted by a journey to the realm of the dead. This type of genesis narrative also supports an understanding that every part of the physical world holographically reflects the pattern of spiritual creativity on a cosmic level.

For proto-Shintō the intersection of the dualities—humanity/nature, spirit/matter, good/bad, alive/dead, above/below, natural/cosmic—is almost always a preexistent intrinsic relation that is not made but discovered, not fixed but evolving, not given but nurtured. In the final analysis, reality is not a world of discrete things connected to each other, but more a field of which we are part (a field often expressed by the indigenous word kokoro). This form of relation applies to the word-reality relation as well. From what we know of proto-Shintō ritual forms, it seems incantations played a central role in purification rites. In those incantations the sounds of the words were, as in magical cultures elsewhere in the world, thought to have special efficacy beyond the simple semantic meaning. Koto was a term for both word and thing suggesting that words had the spiritual power (tama) to evoke, and not simply refer to, a preexisting reality. Thus, the term kotodama (koto + tama) suggested an onto-phonetic resonance reflecting internal relations among language, sound, and reality.

Although many such characteristics of proto-Shintō are found in other archaic animistic cultures throughout the world, unlike many of those other locations, in Japan those ancient sensitivities were not suppressed by the imposition of rationalistic philosophies from outside. For example, the expansion of Christianity with its Greco-Roman philosophical analyses drove underground many older animistic cultures (such as the Druids in the British Isles). When the major philosophical traditions from continental Asia entered Japan, by contrast, they did not take an oppositional stance toward the world view already in place within the archipelago. Therefore, much of proto-Shintō’s organicism, vitalism, and the sensitivity to the field of inter-responsive, internal, and holographic relations could survive within the mainstream of Japanese thinking.

3.2 Confucianism

The impulse to philosophize in an organized fashion came to Japan in waves from continental Asia: China, Korea, and indirectly India. Previously illiterate, in the fifth century or so the Japanese started developing a writing system, using at first the Chinese language for its base. Because Japanese and Chinese are linguistically unrelated and differ both syntactically and phonetically, it took centuries for a Japanese writing system to evolve out of the Chinese sinographs, in the meantime making Chinese the de facto written language. As such, Chinese philosophical works served as textbooks for Japan’s study centers, eventually transforming the culture beyond the parameters envisioned by the proto-Shintō world view and forms of life.

Of the three classical “Ways” of traditional Chinese philosophy, namely, Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, only the latter two achieved independent prominence in Japan. Daoism contributed to the proto-Shintō base a more sophisticated understanding of the processes of natural change and a conceptual vocabulary for creative, responsive engagement with reality through agenda-less activity (what the Chinese Daoists called wuwei). For the most part, however, its influence was most obvious in the alchemical arts, prognostication, and as a resource for occasional literary references. Admittedly, in the medieval period some Daoist philosophical references appear in the language of the arts, especially in theories of creativity, but they occur mainly within a Zen Buddhist context. That is likely because before coming to Japan, Chinese Zen (Chan) had already assimilated many Daoist ideas. In contrast with Daoism, however, Confucianism and Buddhism maintained a presence throughout Japanese history as independent philosophical currents of philosophy. Of the two, we consider Confucianism first. (See also the entry on Japanese Confucian Philosophy.)

As the second fountainhead of Japanese philosophy, Confucianism entered the country as a literary tradition from China and Korea beginning around the sixth and seventh centuries. By then it already enjoyed a sophisticated continental philosophical heritage well over a millennium old. Confucian philosophy in Japan underwent only minor changes until its second wave in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries after which it experienced major transformations as it became Japan’s dominant philosophical movement until the radical changes brought by the modern period. With the Meiji Restoration of 1868, that is, with the overthrow of the shogunate and the return of imperial rule, Confucianism receded somewhat in its philosophical dominance, yielding to the rise of Western academic philosophy, State Shintō ideology, and the secularized version of bushidō (Way of the warrior) as promulgated in the educational program of National Morality. That is not to say, however, that Confucianism did not continue to remain influential in its emphasis on scholarship, the definition of hierarchical social roles, and general models of virtue.

The Confucian Social and Moral Order

From the time of their introduction into Japan, Confucian political, social, and ethical ideals quickly transformed the structure of Japanese society. From the seventh century, texts traditionally associated with Confucianism served as the core curriculum in the imperial academy for the education of courtiers and bureaucratic officials. Politically, Confucian ideology gave a sophisticated justification for an imperial state. Like proto-Shintō, it recognized the charisma of the political ruler as both a chief ritual priest and mediator with the celestial realm as well as the pinnacle of political authority. But Confucianism added to the Japanese context a rich description of political and social roles that organized the society into a harmonious network of interdependent offices and groups. Confucianism defined a place for each person and a set of shifting roles and contexts to be performed with ritual decorum.

So the proto-Shintō taboo structure was enhanced with a Confucian set of socially appropriate behaviors. Once again, it was not a matter of moral mandates about good vs. evil, however, but a description of role-based behaviors describing rightness as contrasted with inappropriateness or impropriety. Those dimensions of Confucianism could be assimilated into the proto-Shintō world view as useful elaborations and improvements, especially ones that would enable the growth of a Japanese state that expanded beyond family and regional clan regimes to become a central imperial state spanning the archipelago. Furthermore, as it became aware of the high cultural achievements of its Korean and Chinese neighbors, Japan could use Confucianism to participate in the East Asian cultural sphere defined by China and the prestige accompanying that membership.

One striking exception to the adoption of the standard Confucian political philosophy was that the Japanese ignored the principle of the mandate of heaven (tianming in Chinese) that was central to the Chinese Confucian ideology of the state. In China the authority of the emperor flowed from a celestial entitlement or command, a mandate that could be withdrawn if the emperor no longer acted in accord with the Way (dao) or cosmic pattern (tianli). By contrast, following their proto-Shintō sensitivities, the Japanese understood imperial authority to derive primarily from the field that included the internal relations among heaven and earth or the deities and the people, with the emperor’s being considered a direct descendant of the celestial sun kami, Amaterasu. Indeed, proto-Shintō considered the relation between the celestial kami, the emperor, and the people to be familial and in no way either contractual or transcendent. Like a blood connection, all Japanese and the kami were, through the emperor, internally related with each other such that the connections among them could not be nullified.

Not having a philosophical tradition of its own, proto-Shintō did not so much argue against or refute the Chinese idea of the mandate of heaven; it simply ignored it, however fundamental it was to Confucian political theory. It is significant that no major Confucian thinker, not even in the most ascendant period of Confucian philosophy under the Tokugawa shogunate, vigorously argued that the mandate of heaven should supersede the Shintō justification for imperial rule based in the function of the emperor as holographically reflecting the ontological, inherent connection among the kami, the Japanese people, and the physical land of Japan.

For the most part, Confucianism brought to proto-Shintō a new set of detailed ideas about how to organize a harmonious hierarchical society in which roles of respect directed to those above were reciprocated by roles of caring directed to those below. The analysis was that society can be construed as constructed out of five binary relations: ruler-subject, parent-child, husband-wife, senior-junior, and friend-friend. If those five relations are lived with ritualized propriety and an attention to being appropriate to the roles they name (a praxis called in Japanese seimei “trueing up the terms” or “the rectification of names”), harmony will prevail not only in those relations but in the whole society constructed out of those relations. An implication of the Confucian view of role-based ideals is that the sharp separation between the descriptive and the prescriptive collapses. There is theoretically no gap between knowing what a parent (or a ruler, or a husband …) is and the role that person should perform. Thus, Confucianism can be understood as a type of ethico-political utopianism, but it is emphatically insistent that it is based neither in speculation nor rationalistic theory, but in historical paradigm. The prototype is found in the harmonious society depicted in the ancient Chinese classics: the histories, the odes, and the rites that inspired Confucius’s insights. It follows that the Way to become ethically and politically accomplished is to study the classics and to model oneself after the ancient paradigms of the roles exemplified by the sages of the past.

3.3 Buddhism

The third major fountainhead feeding into Japanese philosophy from ancient to contemporary times has been Buddhism. With origins in India going back to the fifth century bce, Buddhist philosophy like Confucianism entered Japan via Korea and China in the sixth and seventh centuries. In contrast with Confucianism, however, by the end of the eighth century Buddhism emerged as the major focus of Japanese creative philosophical development as imported Chinese Buddhist schools of thought were modified and new Japanese schools developed. Buddhism continued its intellectual dominance until the seventeenth century, then making way for the second wave of Confucian ideas that better suited the newly risen urbanized, secular society under the control of the Tokugawa shoguns. With notable exceptions, in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries Buddhist intellectuals retreated from philosophical innovation to focus on institutional development, textual studies, and sectarian histories. When Western philosophy surged into modern Japan and its newly established secular universities, some influential Japanese philosophers saw Buddhist ideas as the best premodern resource for synthesis with Western thought. In some cases that entailed reformulating traditional Buddhist ideas in light of Western philosophical categories. In other cases, philosophers used allocation, relegation, or hybridization to create new systems that tried to assimilate Western ideas while maintaining aspects of traditional Japanese values. That said, in the modern era under the ideology of State Shintō, Buddhism as both a religion and a philosophy often suffered persecution and it was not until 1945 that it was once again completely free to develop its theories openly without government surveillance and censorship.

Buddhism and the Self-World Interrelation

Buddhism, with a millennium of philosophical roots going back to India and further cultivated in China and Korea, brought to Proto-Shintō’s vague intuitions and inchoate belief systems sophisticated analyses, multiple theoretical formulations and counterarguments represented by a multitude of different schools of thought, and a rich new vocabulary redolent with allusions to ideas and terms from Sanskrit, Pali, and Chinese. There were, however, a few nearly universally accepted Buddhist themes that resonated well with the Japanese preliterate context and have continued to influence major lines of Japanese thinking throughout its history

First is the Buddhist claim that reality consists of a flow of interdependent, conditioned events rather than independent, substantially existent things. Nothing exists in and of itself and there is no unchanging reality behind the world of flux. The Buddha’s view was formulated originally in opposition to an increasingly orthodox emphasis in Indian philosophy at the time (roughly the 5th c. bce) that favored the idea of a permanent reality (Sanskrit: brahman) or Self (ātman) behind a world of apparent change. Thus, more than a millennium later Buddhism came to Japan with fully developed, sophisticated analyses supporting a world view that was essentially consistent with proto-Shintō’s unreflective emphasis on internal relations, fluid boundaries, and a field of shifting events rather than fixed things. Moreover, within the variety of Buddhist schools introduced into Japan by the eighth century, there were further resources that could philosophically justify and elaborate what had been rather inchoate assumptions of pre-Buddhist Japan. For example, the Japanese Kegon (Chinese: Huayan) school had a rich philosophy of interdependence based in holographic relations, which had probably been more a magical modality than philosophical idea in the proto-Shintō consciousness. Kegon gave it a philosophical articulation and justification.

A second Buddhist premise is that reality presents itself without illusion in its so-called as-ness or thusness (nyoze; Sanskrit: tathatā). That premise contrasts with a widespread orthodox Indian view (found in the Upaniśads and later Vedas, for example) that reality continuously hides its true nature through illusion (Sanskrit: māyā). Still, according to Buddhism, despite the lack of ontological illusions, we ordinarily almost never access reality as it is because we project on it psychological delusions fueled by habituated stimulus-response systems based in ignorance, repulsion, and desire. As a result, a major theme in Buddhist philosophy is to understand the bodymind mechanisms of the inner self or consciousness, to recognize how our emotions, ideas, mental states, and even philosophical assumptions color our perceptions of reality. The problem is not illusions within reality, but the self-delusions we mistake for reality. Buddhism brought to Japan not only an awareness of the inner dynamics of experience, but also a collection of epistemological, psychological, ethical, hermeneutic, and metaphysical bodymind theories and practices aimed at understanding and eradicating those delusions. Without those delusions our bodymind would be in accord with the way things are and we could live without the anguish created by trying to live in a concocted reality we desire instead of reality as it is.

A third general Buddhist contribution to Japanese thought since ancient times is its theory of volitional action or karma (gō). Every volitional thought, word, or deed has an impact on the bodymind system such that present actions lead to propensities for future actions within that system. Furthermore, karma is Janus-headed in its causality such that those present actions are also in part conditioned by previous volitional actions as well. The result is that I affect my surrounding conditions even as those surrounding conditions are affecting me. Thus, the Buddhist theory of karmic action implies a field of interresponsive agency that is paradoxically both individuated and systemic, both volitional and conditioned. That paradigm has raised a number of issues and generated multiple theories by Japanese Buddhist ethical and social philosophers through the centuries.

3.4 Western Academic Philosophy

The fourth major source of Japanese philosophy, the first of the two additional ones to enter modern Japan, has been the aforementioned influx of Western philosophy into the universities. As tetsugaku, Western philosophy became a standard discipline in the newly established Japanese universities designed on Western models. The philosophy courses, like most other subjects of Western origin, were initially taught by Westerners, mainly professors from Germany and the United States who came to Japan to teach the discipline in their native languages. To prepare students to benefit from that instruction, the government established a comprehensive system of preparatory academies (“higher schools”) scattered throughout the land in which the highly qualified were trained not only in the basic academic disciplines of arts and sciences (both Western and East Asian) but also in the Western languages required for university instruction. Then after completing training in philosophy at the Imperial University (Tokyo Imperial University was the first, then several others were added in other major cities around Japan), the most promising students were sometimes sent abroad to the West for further study, after which time they could assume professorships back home. Thus, as in other academic fields, philosophers in Japan were groomed in Western studies from their early teenage years until their mid- or late twenties. As a result, their philosophical education was truly global in scope.

Western Academic Philosophy and Modernization

Although Roman Catholic Christian thought was introduced by missionaries in the fifteenth century, it had a short-lived influence of about a century before it was banned as part of the closure of Japan to almost all foreign contact. Hence, the first strong and lasting impact of Western philosophy came in the late nineteenth century. Although its impact has been broad and difficult to summarize, a few key points are especially noteworthy.

First, in the two or three centuries preceding the modern period, Confucianism and its secular academies dominated the philosophical scene. Since Confucian philosophy placed a premium on the mastery of classic historical texts and given the etymology of the neologism tetsugaku, it is probably not surprising that the study of the history of Western thought was one pillar of the Japanese philosophy curriculum. Many young philosophers could read the original texts in English, German, or French and sometimes also in Greek or Latin. For a wider audience, there was a major publication effort to translate major Western philosophical works into Japanese. With Japan’s new openness to Western ideas, modernization, and the democracy promised in the Meiji Constitution of 1889, there was initially an attraction to the liberal political ideas of Rousseau and J. S. Mill, for example.

Second, the stress on urgent technological and scientific development as well as the chance to break free from the canonicity of Confucianism (and to a lesser extent Buddhism) led to an almost immediate interest in Comte’s positivism and Mill’s utilitarianism. With the new emphasis on mathematics and science, there was also an interest in the new (still “philosophical”) field of experimental psychology represented by Wilhelm Wundt and William James.

In the long run, however, German philosophy, especially German idealism had the most lasting and deep influence. This was partly a fortuitous connection brought about by the close association formed in the late nineteenth century between Tokyo Imperial University and Germany. Not only were some key early foreign professors at Tokyo from Germany, but also Germany became the favored location for sending Japanese philosophy students for foreign study. Another factor was the modernization strategy of Japanese government and intellectual leadership. To modernize as quickly as possible, a Western country was identified as the model to emulate for each academic field. For example, for medicine and physics, Germany was the target; for government bureaucracy, France; for agricultural science and public education for school children, the United States. Once the decision was made, urgency made it difficult to change direction. And Germany was chosen for philosophy. In that context even more than Plato or Descartes, Kant was considered the key figure for the founding of tetsugaku. He had settled the challenge of Hume’s skeptical stance toward science, saved us from scholastic theological metaphysics by establishing critical philosophy and the antinomies, as well as given direction––either positive or negative—to the development of Fichte’s philosophical anthropology, Hegel’s dialectical thinking, Schopenhauer’s and Nietzsche’s Will, Kierkegaard’s subjectivism, and the later school of neo-Kantianism. At least that became the mainstream view among the majority of Japan’s early twentieth-century philosophers.

3.5 Bushidō (The Way of the Warrior)

The fifth fountainhead of Japanese philosophy did not originate from abroad but bubbled up from within Japan itself in the modern period: bushidō, the Way of the warrior. Although there had been edifying handbooks and martial codes in Japan for centuries preceding the modern period, bushidō was formalized only in the modern period as a school of thought with a political, ethical, and ethnic ideology in service of the state. Loyalty was originally a generalized lower-order Confucian virtue but bushidō gave it a special meaning by linking it directly to the emperor and the holographic paradigm supporting the imperial system in State Shintō. The emphasis on dying as the fullest expression of loyalty seems to have been most foregrounded in 1701 with the famous Akō Incident of the Forty-seven Masterless Samurai, later valorized in popular literature and dramatic performances. A contributing factor in that cult of death may have been the emphasis on the death of the ego-self in Zen Buddhism, a locution used by Rinzai Zen masters in training unemployed samurai who joined the monastery during the centuries of the Tokugawa peace. In addition bushidō emphasized the value of makoto, genuineness or trustworthiness, a term with originally Shintō connotations. Added to those native influences was the imported nineteenth-century European ideologies of ethnic virtue, the purity of a given race of people as constituting the basis for a nation state.

Bushidō and National Morality

Bushidō philosophy is, therefore, a true hybrid of Confucian, Buddhist, Shintō, and European parentage. Ideologically it claimed to have been a philosophy of the Japanese people harking back to ancient times but its parentage is clearly nineteenth century. Because of its hybridity, however, its history was occluded and its tenets were couched in terms deemed traditional but often given nuances they had not had previously. Hence, bushidō was almost impervious to philosophical critique, especially when it was protected by government censorship and institutionalized in the mandatory national educational curriculum for school children called National Morality. In an important sense it is not at all a philosophical stream comparable to the others, but its impact should not be overlooked because it did affect the flow (and the stagnation) of the other streams for the first half of the twentieth century. That brings us to an overview of the eddies and cross-currents of the five streams in Japanese history.

4. Historical Periods of Philosophical Development and Interaction

4.1 Ancient and Classical Philosophy (up to 12th century)

The ancient and classical periods of Japanese philosophy span the years 604 (the traditional date of Shōtoku’s Seventeen-article Constitution) to 1185 (the fall of aristocratic rule and the installation of the first military shogunate). In the usual Japanese reckoning, it covers the Late Kofun (or Asuka), Nara, and Heian periods. During that time Buddhism came to dominate the philosophical landscape by allocating the social and legal systems to Confucianism and relegating proto-Shintō to a subordinate place within its expanded, all-inclusive system. Prince Regent Shōtoku’s hope, as expressed in his Constitution, was to establish Buddhism as a state religion but to continue state rituals venerating the proto-Shintō kami, while adhering to Confucian ideals (along with some Chinese Legalist ideas) in organizing a centralized state government. Even after Shōtoku’s pro-Buddhist Soga family fell from power, the basic model endured. Chinese laws served as models and Buddhist texts and teachers continued to flow into Japan.

When the first permanent capital was established in Nara in the eighth century, the city plan included a number of Buddhist temples, Shintō shrines, and Buddhist institutes or study centers, including those of the so-called Six Nara Schools (all based on Chinese Buddhist schools with roots traceable to India). Buddhist practice, especially for intensive periods, was often performed in mountain temple retreats in natural settings rather than in the city. Creative and innovative thinking was limited at this point, but that would change with the establishment of two new schools at the beginning of the ninth century, Tendai (founded by Saichō, 767–822) and Shingon (founded by Kūkai, 774–835). Although both traditions originated in China, they assumed distinctively comprehensive Japanese forms that would set the trajectory of Buddhist philosophy in Japan for centuries to come. The major factor behind their success was their focus on “esoteric teachings” (mikkyō). In establishing that core orientation, Kūkai was the pioneering figure and the more sophisticated philosopher, indeed often considered Japan’s greatest premodern systematic thinker. (See the entry on Kūkai.)

4.1.1 Kūkai’s Esoteric Foundation for Japanese Philosophizing

The linchpin in Kūkai’s philosophy was his distinction between engaged and detached knowing, which he formulated in terms of the “difference between esoteric teachings (mikkyō) and exoteric teachings (kengyō).” (See the entry on Kūkai, section 3.2.) The esoteric involves an interpersonal engagement between the cosmos (the activity of patterned, self-structuring resonances called Dainichi Buddha) and the Shingon practitioner (who is a bodymind holographically inscribed with the same pattern as the cosmos). Wisdom occurs when the theory-praxis of the Shingon Buddhist enables the cosmic functions and the person’s functions to be in accord, that is, to resonate harmoniously.

By contrast, Kūkai claims that detached or exoteric understanding occurs when there is a separation between knower and known, a gap that can only be bridged with the external application of linguistic categories or heuristic expressions (hōben; Sanskrit: upāya). So an exoteric philosophy, even if it knows about engagement, cannot ground its own theory in an engaged way because it depends on external relations even to express itself. It is, in effect, a theory about bodymind unity that is based only in the mind. That realization led Kūkai to argue the inherent limitation in exoteric philosophy is what gives rise to it, what in Buddhist terminology is called its mindset (jūshin).

Kūkai used relegation to explain his detailed “theory of the ten mindsets” (jūjūshinron). (See the entry on Kūkai, section 3.12.) He analyzed all the philosophical standpoints known to him into a hierarchy of the ten mindsets producing them, starting from the base level of narcissistic philosophy driven by animal impulses, up through the mindsets of Confucianism, Daoism, and continuing in the hierarchy through all the Buddhist schools existing in Japan at the time. Kūkai ranked Kegon Buddhist philosophy at level nine, the highest level of exoteric thinking because it highlighted internal and holographic relations. Only Shingon’s esoteric philosophy of embodied theory-praxis ranked above it.

In determining his rankings, for each level Kūkai asked whether that mindset could establish its own ground within its own terms. For example, to put one’s own interest above others, the narcissistic mindset (level one) must account for the existence of those others in one’s own awareness. That, in turn, leads to an understanding that the self must be relational, a fundamental assumption of the Confucian mindset found in level two. That is, even the egoism of narcissism, upon examination, assumes a relational self of the sort that is the point of departure for a Confucian analysis. Thus a lack of foundation in mindset one opens to the prospect of mindset two. At the other end of the scale, Kegon Buddhism’s level-nine mindset generates a theory of the interpenetration of all things and the holographic relation of whole-in-every-part, but to do so the mind must stand outside reality to characterize it as such. Yet, its own theory implies the knower cannot be independent of the known, nor the mind from the body. That opens the door to a praxis of engagement that is the basis for the esoteric mindset (level ten).

Kūkai argues the “mind” of the Shingon mindset is more like “bodymind” because it is a knowing inseparable from praxis. Whereas a philosophy based in metaphysical theory can never establish its own ground, a philosophy based in an engaged bodymind praxis can produce its ground as surely as, we might say, the understanding of the master potter is produced in a masterful work of pottery. Whereas the exoteric philosopher, using detachment and assuming external relations between self and reality, presents truth as ideas linking those two relatents, the esoteric philosopher engages self and reality in an internal relation, presenting truth as a unified bodymind performance of thought, word, and deed. In Kūkai’s terminology, “one achieves buddha in, with, and through this very body” (sokushinjōbutsu). (See the entry on Kūkai, section 3.9.)

Although Kūkai’s philosophy itself did not become dominant in the Japanese tradition, he set a pattern for philosophizing that (often without acknowledgment) continued to influence many later philosophers even into modern times. First, he firmly entrenched a preference for internal and holographic relations. Second, he demonstrated that a strong philosophical position should not only be able to show weaknesses in other positions but also, if it is truly comprehensive, it should be able to explain how such an error or misunderstanding could occur. In other words assimilation through relegation is a stronger position than simple refutation because it takes opposing theories as real theories deserving a place within any all-inclusive account of reality. Third, a way to evaluate a new philosophical position is to try to understand the mindset that produced it. That methodological strategy would be especially helpful as Japanese philosophers encountered new theories from other cultures.

As the classical period continued, Buddhist philosophizing was concentrated in the monastic communities, especially the huge mountain complexes of Mt Hiei in Kyoto representing Tendai Buddhism and Mt Kōya representing Shingon Buddhism. At first borrowing from Shingon, Tendai soon evolved its own form of esotericism with additional input from emissaries sent to China for further training. Since Tendai was already the most comprehensive form of exoteric teaching in Japan, when mated with esotericism, it became the most inclusive and comprehensive system of philosophy and praxis in the country. As a result, by the end of the classical period the monastic center on Mt Hiei emerged as the premier site of monastic education and philosophical training.

4.1.2 Aesthetics in the Heian Court

For the lay aristocrats, the Heian court of Kyoto was the hub for the classical study of both Chinese and Japanese arts and letters, becoming a fertile ground for aesthetic theories, some of which were borrowed from China, but others emerging from more native sensitivities. The notion of reality as a self-expressive field—whether formulated in terms of the native idea of kokoro or of the activity of the cosmos-as-buddha, whether seen as permeated with the spiritual power of kami or buddhas, whether relished for the poignancy of its impermanent beauty however fleeting (as in the aesthetic of aware in Lady Murasaki’s Tale of Genji) or seen as a detached object for amusement (as in the aesthetic of okashi in Sei no Shonagon’s Pillow Book)—became a focal point for the cloistered world of the Heian court, generating an artistic sensitivity and vocabulary that became a cornerstone of Japanese aesthetics. As the classical period drew to a close, however, the cloistered worlds of the monastery and the Heian court would come under attack and philosophical innovation would need to find new contexts.

4.2 Medieval Philosophy (late 12th through 16th centuries)

The medieval period witnessed the destabilization of the social, political, and religious order. The luxuries and amusements of court life had become so attractive that many aristocrats abandoned their far-flung estates to spend more time in the capital, entrusting their wealth-generating domains to the hands of their stewards, the samurai (“those who serve”). Eventually, the samurai took over the domains for themselves, then fought each other for national dominance until the Minamoto were victorious in 1185, establishing Japan’s first military government or shogunate in 1192. To protect its vulnerable position, it centered its operations in Kamakura, leaving the court and the emperor in Kyoto. The political instability and the attendant economic upheaval were exacerbated by an unusually devastating period of natural disasters, pestilence, and famine. When personal survival was at stake, the complex theories and practices of Shingon and Tendai Buddhism were of little solace to most people. Furthermore, the financial success of the monastic centers had led to institutional corruption and a popular theory was that Buddhism had entered its final Degenerate Age (mappō) in which teachings were lost, could no longer be understood, and enlightenment no longer attained. Tendai’s Mt Hiei, which had been a magnet for many of Japan’s brightest and most gifted thinkers, started to lose some of its most talented monks as they left the mountain and eventually advanced new Buddhist philosophies resulting in the rise of new religious sects, most notably Pure Land, Zen, and Nichiren.

4.2.1 The Strategy of Selection

Among the founders of the so-called Kamakura New Religions, the Pure Land philosopher Hōnen (1133–1212) expressed a seminal idea that keynoted the greater movement. (See the entry on Japanese Pure Land Philosophy, section 3.) A noted Tendai master of Mt Hiei’s texts and practices, both esoteric and exoteric, he was frustrated with his personal failure to find any liberating insight. As a Tendai philosopher, however, he recognized one teaching that could lead to a new philosophical approach, namely, the holographic paradigm of the whole-in-every-part. Tendai had used it to go from simplicity to reveal ever greater levels of complexity, but might it now also be reversed? Could it not be used to pare complexity down to a minimal particularity that would still be all-inclusive? The key would not be to set out to embrace the whole, but instead to select one thing––one practice, one teaching, one text—and to focus on that, realizing that by the holographic paradigm ultimately nothing would be lost. By that line of thought, Hōnen came to his idea of selection (senjaku or senchaku) as the guiding strategy for his engaged philosophy. By engaging a properly selected single teaching or practice, one does not abandon the holistic view but instead discovers it as inscribed in that particular. That philosophical modus operandi became the guiding principle for all three of the major branches of Kamakura-period philosophies: Pure Land, Zen, and Nichiren.

Selection involves a decision about what to select and a methodology for engaging the selection as a single bodymind focus. Pure Land thinkers like Hōnen and Shinran (1173–1263) concentrated on the mythos of the Vow of Amida Buddha to aid those who could not attain liberating insight by their own devices or efforts and so needed assistance from outside. Since the theory of the Degenerate Age suggested all people were in that state of personal helplessness, Amida’s Vow was intended to serve everyone. For Nichiren (1222–1282), the creator of the Nichiren School, the despair of the Degenerate Age was again a consideration, but in his interpretation, the second half of the Lotus Sutra was written specifically for those times and should be the sole focus of selection. For philosophers like Dōgen (1200–1253), the founder of Japanese Sōtō Zen Buddhism, the theory of the Degenerate Age was irrelevant. As a result, he selected a single practice he considered central to all Buddhist traditions from the outset: the state of bodymind achieved in seated meditation (zazen) under the guidance of a master. (See the entry on Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy.)

The biographies of the Kamakura philosophers suggest that most often their selection process arose from a sudden intuition, or a statement from an inspiring text or teacher, after a frustrating period of trial and error. Since most of them had originally trained at Mt Hiei and because they were deviating from the Tendai Buddhist establishment’s doctrines and practices, they were accused of heresy, which could lead to a penalty of exile or even execution. So they devised ex post facto philosophical justifications for their choices, often explaining how their new selective teachings and methods were consistent with tradition and demonstrating, by using a holographic argument, that nothing significant was really being omitted from the orthodox tradition. The situation resulted in some of the most creative medieval theories of metaphysics, philosophical anthropology, and philosophies about the structures of experience.

As for engaging the selection wholeheartedly in a focused bodymind activity, Hōnen, Shinran, and Nichiren all emphasized “entrusting faith” (shinjin) as the Way that dissolves the ego-self into a focal object. For the Pure Land philosophers, the object is the fulfillment of Amida Buddha’s Vow as expressed in the phrase of the nenbutsu (namu amida butsu “I take refuge in Amida Buddha”), for Nichiren the power of the Lotus Sutra (especially as further holographically particularized in the recitation of its title). In such cases the model of faith is one of internal relations and immersion in immanence rather than one of external relations and faith in a transcendent reality. In the case of Dōgen’s Zen, the engagement in zazen is characterized by a state of without-thinking (hishiryo) in which “bodymind drops away.” In that state of full engagement with as-ness (inmo or nyoze, how phenomena are before they are structured by concepts), one is at the prereflective point that is in itself without meaning, but is the basis from which meaning is generated in any context. That is the “eye for the truth” (shōbōgen) that is the provenance (yue) of both words and praxis. Thus, in Dōgen’s decision to make seated meditation his item of selection, he focused on how to find the experiential point from which full engagement can originate. (Kasulis 2018, 218–34)

One benefit of the Kamakura innovations was that their singular practices were readily accessible to anyone, even the uneducated. Over the centuries, the Kamakura New Religions gradually became the most popular forms of Buddhism in Japan. At the same time, the philosophical justifications for those minimalized practices, the metapraxes, were often highly sophisticated and have continued to attract the further reflection of some of the best philosophical minds in Japan over the centuries. For example, some twentieth-century Japanese philosophers found points of contact between Western existential philosophers’ responses to Angst and the medieval Buddhist philosophers’ responses to the anguish of the Degenerate Age.

4.2.2 Muromachi Aesthetics

With the decline of the cloistered Heian court, the nature of Japanese aesthetics underwent a change as dramatic as that of religious philosophies. After the fall of the Minamoto’s shogunate in Kamakura and the takeover by the Ashikaga, the new shogunate moved its headquarters to Muromachi in Kyoto in 1338. The reestablishment of relations with China precipitated an economic boom and revival of the Chinese-influenced arts in the capital, but the prosperity was short-lived. Triggered by a dispute over shogunal succession, open warfare broke out in Kyoto, ultimately involving most of the major regional military lords from around the country. The capital was leveled and the Ōnin War (1467–1477) ended in stalemate but not before the coffers of the shogunate and the court were almost completely depleted. Upon returning to their home regions, local wars continued and the entire country entered the Period of Warring Domains, lasting for over a century. Without the isolation of a cloistered community of aristocratic courtiers, the former aesthetic categories were superseded by new ones suggestive of retreat or withdrawal: withdrawal from the cultured and elegant to the plainness of the rustic (wabi), withdrawal from the outward glitter to the lonely, neglected, and isolated (sabi), and withdrawal from the surface to the quiet, mysterious depths (yūgen). These became central categories in the new art forms of tea ceremony, poetry, nō drama, and landscaped gardens. (See the entry on Japanese Aesthetics, sections 3–5.)

4.3 Edo-period Philosophy (1600–1868)

The Edo period marked a time of relative peace and stability under the Tokugawa shogunate following the unification of the country by a sequence of three hegemons: Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582), Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598), and finally Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616). Most of the unification occurred at the hands of Nobunaga with Hideyoshi as his chief general. A major factor in Nobunaga’s success was his cunning use of the new technologies of warfare (canons and muskets) introduced by Portuguese traders in 1543.

With the Portuguese and Spanish ships came Roman Catholic missionaries. The hegemons at times welcomed the Christians as informants about the West and as foils against Buddhism, but at other times, viciously persecuted them as potential threats in turning the people against the new political order in favor a foreign God. In the end, Christianity was banned from the country entirely (with most finality after the closure of Japan to almost all Western contact after 1637). Therefore, although Christianity enjoyed some initial success in its number of conversions, its overall impact was limited. Formal polemical debates with Buddhists did introduce some new lines of argument to Japan especially concerning creation, afterlife, and teleology. Snippets reappeared in later Shintō arguments, most notably those by Hirata Atsutane (1777–1843), but in general, as a philosophical tradition, Christianity’s impact would be minimal until its reintroduction to Japan in the modern period. The major philosophical innovation of the Edo period would not be Christianity but rather a new form of Confucianism.

4.3.1 Edo-period Confucianism